Home » Articles posted by Alan Schwartz (Page 3)

Author Archives: Alan Schwartz

Alan on Catskill Review of Books, and a letter to NYT

This week, Alan Schwartz was interviewed by Ian Williams at the Catskill Review of Books about Listening for What Matters, and the New York Times published Alan and Saul’s response to Dr. Robert Wachter’s opinion piece How measurement fails doctors and teachers.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/243119710″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

Saul Weiner on Saturday Night with Esme Murphy

Saul spoke with Esme Murphy on WCCO Radio CBS Minnesota on January 16, 2016 about contextual error, unannounced standardized patients, and the book.

Saul on Minimally Disruptive Medicine blog

Saul discusses the relationship between our 4C approach to measuring contextual care and the Instrument for Patient Capacity Assessment (ICAN) from the Mayo Clinic’s Knowledge Evaluation Research Unit on the Minimally Disruptive Medicine blog.

Nobody wants this at the doctor’s office

My father called my attention to this week’s Sunday Dilbert cartoon:

It’s probably intended to point out that when we ask a co-worker “How are you?” we’re not really expecting an answer, just an acknowledgment of the question (“Fine”).

But my father, newly sensitized to contextualization of care, saw that the bearded co-worker is pouring out critical life context here — which Dilbert proceeds to ignore.

The flavor is very much like the examples we’ve seen in our recordings of physician-patient encounters in which a patient drops a clear clue that life context may be impacting his/her health, and a physician proceeds blithely to the next item on the checklist on the electronic medical record computer screen. Would you be surprised to learn that Dilbert’s co-worker’s previously well-controlled diabetes has taken a turn for the worse?

Guest post at The Health Care Blog

What we’ve learned about contextuaized care as a result of direct observation and why we need more: http://thehealthcareblog.com/blog/2015/12/21/this-visit-may-be-recorded/

Context and Diagnostic Error

The Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences (now called the National Academy of Medicine) has just published an important viewpoint article in JAMA about measuring diagnostic errors.

The authors, McGlynn, McDonald, and Cassel, point out that diagnostic errors have received less attention than treatment errors, but are very common and can lead to incorrect treatment and unnecessary costs and harms.

Our work suggests that failure to contextualize care plays an important role in diagnostic error. The article lays out five reasons to measure diagnostic errors, each of which also speaks to the need to better measure and understand contextualization of care:

- Establish the Magnitude and Nature of the Problem

- Determine the Causes and Risks of Diagnostic Error

- Evaluate the Effectiveness of Interventions

- Assess Skills in Education and Training

- Establish Accountability for Diagnostic Performance

Readers familiar with our work will recognize studies of contextual errors that have focused on each of these issues. In our own research publications, we have demonstrated that contextual errors in diagnosis (and therefore, inappropriate management) occur frequently, contribute to unnecessary health care costs, and are associated with worse outcomes for patients. We have also demonstrated several educational strategies that have promise for reducing these errors, and have discussed direct observation of care as a critical missing component of measuring performance. In our forthcoming book, we further discuss causes of contextual errors in diagnosis and the need for systems of medical education and healthcare delivery to apply strong measurement tools to reduce these errors.

The work of this IOM committee is an important effort to bring light to an understudied but serious problem in health care.

Schwartz to receive John M. Eisenberg Award

I’ve recently learned that I will receive the John M. Eisenberg Award for the Practical Application of Medical Decision Making Research at this year’s Society for Medical Decision Making meeting in St. Louis Oct 18-21. John Eisenberg was a pioneer in medical decision making, health services research, and quality measurements. Much of his later work focused on understanding and incorporating patient values and outcomes in both clinical and policy decision making.

In my award address, I will be talking about the importance of keeping the focus on people in conducting applied research – and specifically about contextualizing care.

Curious health providers also provide better care

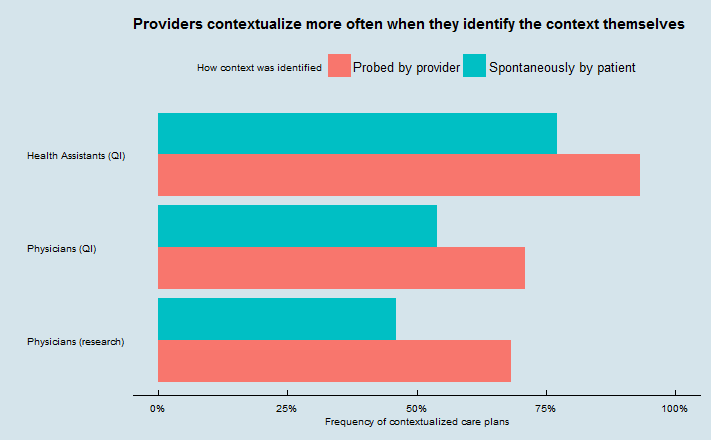

There are two ways to learn what is really going on with another person who seems to be struggling: by asking them or by waiting for them to tell you. It turns out that when care providers are proactive and ask first, they are also more likely to help others cope with their challenges.

Our findings are in a new paper in a new paper in BMJ Quality & Safety. Specifically, we tracked how health assistants and physicians reacted to verbal cues that something in a patient’s life may be affecting their health care (what we call “contextual red flags.”) Providers who asked about these contextual red flags were more likely to act on what they learn than when their patient volunteers the information without being asked. For instance, if a patient has lost control of his diabetes (a contextual red flag) because he started working the night shift which has disrupted his diet, the physician is more likely to adapt the care plan if she learns about the life change by inquiring rather than having to be told.

How much more likely you ask?

This is the kind of phenomenon that you can only discover by directly observing patient-provider interactions. We found this pattern by reviewing audiorecordings made during three different sets of encounters.

This is the kind of phenomenon that you can only discover by directly observing patient-provider interactions. We found this pattern by reviewing audiorecordings made during three different sets of encounters.

Two sets were recordings of visits between patients and physicians (209 visits from our research, and 1183 visits from a quality improvement project focused on improving contextualization), and one set was recordings of 96 telephone calls from clients to Accolade health assistants.

(Accolade is a novel company that contracts with employers or payers to provide telephone health assistants to aid employees/members with healthcare and claims needs. As you can also see from the chart, their health assistants do very well at contextualizing their advice – so much so that with their higher overall contextualization rate, 96 calls is not quite enough to call the difference in the chart significant using Accolade data alone. Full disclosure: our company, I3PI, consults for Accolade and had helped them study contextualization several months before we got the idea for this paper).

We found that value of physicians or other care providers actively asking patients about red flags that lead them to reveal relevant contextual information is not simply in the context that is revealed. The act of asking is associated with a greater chance that the context will actually be used to tailor plans of care. This could be because providers who are attuned to the importance of context do more asking and more tailoring than those who are not, or could be because asking and getting a positive response makes the context more salient (or both). Of course, it could also mean that providers only ask about context that they already know to how use.

Our take-home message: Providers should be encouraged both to ask more about potential context and to listen more when patients reveal it themselves.

It really is the patient’s story

Attitude toward illness is one of the ten domains of context that we’ve documented in our work studying physicians’ skills at tailoring care to real patients’ needs. One thing that we often don’t appreciate is how important it can be for people to be able to explain their choices – not only to others, but also to themselves, in light of their past experiences and choices. We often experience our lives as unfolding stories, and we want those stories to make sense to us.

A recently published article in the journal Medical Decision Making looks at this (full disclosure: I am the editor-in-chief of that journal). In “My Lived Experiences Are More Important Than Your Probabilities: The Role of Individualized Risk Estimates for Decision Making About Participation in the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR)“, Christine Holmberg and colleagues interviewed women who agreed or declined to participate in a trial of tamoxifen and raloxifene, medications that are used to reduce the risk of breast cancer but have potential side effects. These drugs appear to be underused, based on statistical evidence about the number of women who would, on the whole, benefit from them.

When they asked women about their decisions to join or decline the trial, they found that personal or family experiences with breast cancer and general concerns about the effects of taking medication were more important than information about the probability of breast cancer or side effects. The authors refer to this as “a decision-making process for or against STAR participation that was guided by personal experiences, attitudes, and beliefs.” Those who joined the trial and those who didn’t came to different decisions, but did so through similar considerations about their individual life context.

This work is in the tradition of decision psychology research by Nancy Pennington and Reid Hastie in what’s been called “explanation-based decision making” or the “story model”. Most often studied in jurors or consumers, the idea is that sometimes what seems to be important to people in their decision making is that they be able to explain their decisions – not only to others, but also to themselves. People want to place their choices in the context of their identity and lived experience, which is itself shaped by their past choices.

Combine these theories with work on “illness narratives” pioneered by Arthur Kleinman, and research on identity in health psychology, and the message is clear: no matter how “right” a choice may be on the evidence, it’s very hard for people to do it if it contradicts their personal story.

Physicians looking to engage with their patients need to be listening for these stories too.

Welcome

Welcome to the Contextualizing Care blog.

Most of us have consulted a physician at some point; many of us wonder whether our physicians’ recommendations could have been better tailored to our circumstances and needs. As medical educators and health care researchers, we have made improving the contextualization of care an important focus of our career.

We know that doctors want to treat patients as individuals, and to provide the best care for each patient. But we also know that the systems and structure of medical practice, payment, and training work against individualized care. Through our research studies, we have demonstrated that the failure to contextualize care is common, costly, and leads to worse health for patients. Through our book, Listening for What Matters, and this blog, we hope to share these insights and to explain our vision of how medical care and medical education can reclaim the focus on individual patient context. We hope we will spark a discussion among patients, physicians, payers, and policymakers about what it means to practice patient-centered medicine.

We know that doctors want to treat patients as individuals, and to provide the best care for each patient. But we also know that the systems and structure of medical practice, payment, and training work against individualized care. Through our research studies, we have demonstrated that the failure to contextualize care is common, costly, and leads to worse health for patients. Through our book, Listening for What Matters, and this blog, we hope to share these insights and to explain our vision of how medical care and medical education can reclaim the focus on individual patient context. We hope we will spark a discussion among patients, physicians, payers, and policymakers about what it means to practice patient-centered medicine.